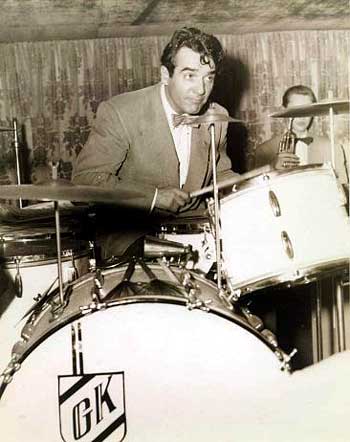

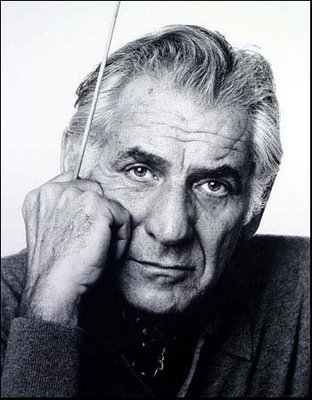

Gene Krupa and Leonard Bernstein

As a kid with eclectic tastes growing up in a musical family, I never thought about one genre being better or more important than another, or that musical genres needed to remain segregated, that merging them amounted to sacrilege. After playing percussion in youth orchestras, drums in various rock and soul bands, and piano in a jazz trio, I was in my mid-20s before I finally assembled a band that could play the smorgasbord of music I’d been composing since age 10.

The band featured a guitarist who’d studied with Pat Metheny at the Berklee College of Music, a bassist who at age 17 had created the electronic-music lab at Rutgers University, a keyboardist with classical chops who, as a white kid, had played gospel piano in black churches, and a violinist from the San Diego Symphony. Those diverse influences and backgrounds were perfect preparation for creating original, hybridized music, which, to us anyway, was completely natural.

So it always struck me as bizarre when I’d hear about musical “balkanization,” of concerted efforts to keep different types of music compartmentalized and isolated. And it infuriated me in the ‘70s when such “progressive-rock” bands as Yes, Genesis, Gentle Giant, and Emerson, Lake, and Palmer were automatically deemed “pretentious” by many critics and rock adherents for incorporating their own varied tastes, influences, and musical educations into the rock paradigm. As was the case so many times before in music’s evolution, introducing fresh, new ideas to rock and roll apparently threatened the comfortable status quo of this presumably rebellious music, making progressive practitioners — at least in some quarters — more pariahs than pioneers.

When I first became aware of the “Third Stream” music of the late-’50s and early-’60s, I was struck both by the underlying logic of bridging the classical and jazz worlds, and by its ultimate failure to catch on. When deconstructed, both jazz and classical music boast groundbreaking, immortal music and jaw-dropping virtuosity. If jazz’s emphasis on improvisation is an important distinction, it’s not necessarily a deal-breaker, especially when you consider that Handel, Bach, Beethoven, Mozart, and Haydn were notable improvisers. American-born musicologist/composer/conductor Gunther Schuller must’ve felt that way, because he not only staked his reputation on creating a successful hybrid of the two genres, he even is credited with coining the term, Third Stream.

Of course, very little classical music has been created in a vacuum, and the introduction of non-classical elements to classical music is as old as the music itself. Many famous pieces are based on the traditional folk music of the composer’s homeland, or were inspired by visits to other countries. Popular dance music, especially, has been a favorite source material for centuries; Bach had the Sarabande, Chopin had the Polonaise, and Vienna’s Johann Strauss, Jr. had the waltz, which had its roots in 16th-century peasant dances. So it was only natural that when ragtime, early jazz, and the Charleston became the rage in America and Europe, 20th-century composers who were seeking new ideas began incorporating those rhythms and phrasings into their work.

In the 1920s and early ‘30s, attempts at classical-jazz or jazz-classical fusion were made by such so-called “serious” European composers as Darius Milhaud, Bohuslav Martinu, Matyás Seiber, Emil František Burian, and Stefan Wolpe, as well as by Americans George Gershwin and Aaron Copland. One of the most important of these figures was Hungarian-born Seiber, who considered jazz an art form when most people did not. Seiber became head of the first jazz department in a German conservatory, teaching and composing in Frankfurt at the same time that a Frankfurter named Theodor Adorno was making public pronouncements that jazz was anti-intellectual and provided a sense of “false freedom” for soloists.

Seiber ignored Adorno’s 30-year rant, as well as the defamation he later suffered in the Nazi press for his associations with jazz, and went on to write some of the finest music of his day. In the second installment of a show I call “Passing the Baton: Jazz Meets Classical at Midstream” (Johnny D’s Jazz Journal, May 26, 2013, 3-5 p.m.), I aired Seiber’s “Jazzolette #2”, written in 1932 and performed by a Dutch ensemble called Ebony Band, comprising members of Amsterdam’s Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra (under the baton of Werner Herbers, who founded the group in 1990). It’s on the CD, Dancing: The Jazz Fever of Milhaud, Martinu, Seiber, Burian & Wolpe (2011, Channel Classics import label).

A decade later, Russia’s Igor Stravinsky composed his Ebony Concerto for clarinet and jazz band for Woody Herman and his orchestra, and Polish pianist/composer Wladyslaw Szpilman (the inspiration for Roman Polanski’s Oscar-winning film, The Pianist, starring Adrien Brody), drew inspiration from jazz.

But Schuller’s later advocacy was significant for its missionary-like zeal. He actively sought a middle ground between the two musics, and to that end, co-founded the Modern Jazz Society with jazz pianist John Lewis in 1955. Lewis’s band, the Modern Jazz Quartet, became a standard-bearer for the hyphenate subgenre, even titling one of its albums, Third Stream Music. For their efforts, MJQ was by some for being musically conservative in the wake of the adventurous work of Charlie Parker and others, and their almost neoclassical approach earned the not altogether complimentary label, “chamber jazz.” But the foursome persevered as tastes continued to evolve, and the MJQ outlasted its detractors to become one of jazz’s most popular and critically lauded groups.

Still, for various reasons, Third Stream never truly caught on. Some listeners found Schuller’s middle ground an academic no-man’s-land in which the two musics’ strengths were canceled out rather than intensified. Certainly, the genres are not easily bridged, in part because a number of musicians on either side of that aisle always will regard the other genre somewhat warily.

It’s also possible that ethnic and nationalistic biases came to bear. Classical music is, after all, a European construct, and jazz is an American, and specifically an African-American art form born of a very Yankee strain of spirited, spontaneous expression. So it would make sad sense if jazz musicians considered the infusion of high-brow “foreign” music the creative equivalent of adding starch to a favorite comfy shirt. Conversely, conservatory-trained classical musicians and composers would have reason to balk at melding centuries of musical tradition and a deep canon of style and content with a renegade form of music that took shape in brothels, saloons, and on street corners.

And maybe, just maybe, people in the 1950s had already been turned off by the ongoing debate between the two camps, which at times grew pretty clamorous. As far back as 1947, drummer Gene Krupa and then-up-and-coming conductor Leonard Bernstein had heated, public exchanges on the relationship between jazz and classical music. The intelligent and articulate Krupa, who listened almost exclusively to symphonic music at home, and, like Bill Evans, could expound on Ravel or Grieg as astutely as he could on Armstrong or Ellington, thought there was little or no trace of jazz in even the most touted jazz-influenced orchestral works.

“Leonard Bernstein and others profess to hear traces, echoes, derivations of jazz in [the music of] Frederick Delius, John Alden Carpenter, Manuel de Falla, Honeger, Prokofiev, even Shostakovitch,” Krupa told Down Beat editor Gene Lees during a series in interviews conducted at recording sessions and backstage at New York’s Capitol Theatre. “I disagree. I’ve never heard anything genuinely and honestly derivative of jazz in any such music, even, maybe especially, in such works as Igor Stravinsky’s Ebony Suite...I’ve never heard it in a single one of the ‘serious’ pieces of George Gershwin...I’ve never heard the least echo of [jazz], or any music like it, in [Maurice Ravel’s] compositions.

“Jazz cannot be approached from the outside,” Krupa said. “It cannot be approached synthetically and artificially. Above all, it cannot be approached unsympathetically. Too many ‘good,’ ‘pure’, and ‘serious’ musicians...approach the native American idiom, the jazz idiom, with intolerance, even with condescension. They stoop, but not to conquer. And so, they almost invariably make an unholy mess of their attempts.”

Bernstein, who actively incorporated jazz elements into his orchestral compositions, strongly held the opposite view. He believed that jazz greatly influenced modern classical music even when that influence might be difficult to pinpoint.

“My old piano teacher, Heinrich Gebhard, used to say that music is divisible into melody, harmony, rhythm, form, counterpoint, and color,” Bernstein wrote in an Esquire magazine essay. “Jazz has influenced our composers on all six counts.” He added that rhythm was the “most important” of these influences, and went on to explain how jazz-derived syncopation (the placement of accents on weak beats or in unexpected places) “opened up new vistas for the serious composer.” He concluded his treatise with a declaration that seemed aimed at his good friend, Gene Krupa — that jazz components had “unconsciously become common usage among American composers. And the startling thing is that very rarely does this music sound like jazz!”

If the jazz-versus-classical debate no longer rages as it once did, perhaps that’s because many musicians who’ve emerged in the last three or four decades — Claude Bolling, Lalo Schifrin, Keith Jarrett, Wynton Marsalis, Chick Corea, Joshua Redman, Chris Botti — seem perfectly comfortable tapping each genre for inspiration, even crossing over from one to the other when the mood strikes. If nothing else, that continuing development will give me plenty of source material for future installments of “Passing the Baton: Jazz Meets Classical at Midstream”. I hope you’ll tune-in.

[If you missed the May 26, 2013 (3-5 p.m.) installment of Johnny D’s Jazz Journal titled “Passing the Baton: Jazz Meets Classical at Midstream”, you can hear it in archived form by signing up for Jazz88.3’s online “Speakeasy” — the free, interactive club that gives you access to on-demand, “Premium Content” and puts you on an exclusive list of people who have a chance at online giveaways. Just click on the “Speakeasy” graphic on our home page at jazz88.org and provide an email address and password. They won’t send you anything and your info will not be shared or sold to anyone — it’s just an extra benefit for Jazz88.3 listeners. Once you’re on the Speakeasy page, scroll down just a bit and you’ll see a list of “Full Programs”. My show is at the top of the right column. Just click on it and you’re listening to that week’s show.]