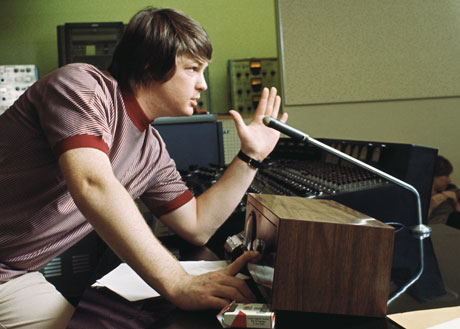

Top left: 1966, Brian Wilson producing Pet Sounds; top right: bassist Carol Kaye (seated, foreground) and musicians during Pet Sounds sessions; above: Brian Wilson today

I didn’t plan my June 16 show to coincide with Father’s Day — it was a coincidence, and, to be honest, a somewhat uncomfortable and cruelly ironic one. I’d been working for weeks on a jazz tribute to a great songwriter, Brian Wilson, founder and creative font of the Beach Boys, who definitely was not lucky in the daddy department. I wanted it to air as close as possible to Brian’s 71st birthday on Thursday, June 20. When my wife reminded me of that June 16 was Father’s Day, I thought, “Uh-oh.”

I considered postponing the show and doing something else on the 16th. But I decided to go ahead with it in the spirit of celebrating Brian’s survival and the contributions he made to the world of music in spite of his childhood. I thought it might give encouragement to listeners who have reasons to avoid Father’s Day, while making others even more thankful for having had good, loving dads, as I did.

Wilson was born in 1942 in Hawthorne, CA, 124 miles up the coast from the KSDS studios in San Diego. He would become one of the most successful and celebrated songwriters of all time, but he definitely got there the hard way. Murry Wilson, Brian’s dad, was a businessman who had aspired to be a songwriter and entertainer. Murry also had been the victim of horrific paternal abuse, so when his show-biz dreams didn’t materialize, he allegedly reverted to learned behavior and took his frustrations out on the oldest, most talented, most sensitive of his three sons, Brian, in physically and psychologically violent ways that I couldn’t describe on the radio and won’t enumerate here.

Brian responded to his anxiety-ridden external reality not by stockpiling weapons or becoming a serial killer, not by mistreating animals or bullying other kids, not by joining a satanic cult or a death-metal band. Brian’s antidote for the horror of his waking life was to retreat inward, to write songs that created an oasis of beauty and peace in the midst of deepening torment, that projected a world of carefree, innocent fun that other teenagers were enjoying, but which, for Brian, was like a party to which he wasn’t invited. Did he become a phenomenal songwriter because of all that, or in spite of it? All I know is that his songs are a formative and influential part of my life’s soundtrack, and I’m certainly not alone.

At 71, Wilson remains musically active; he still releases albums of new music, and last year he reunited with the other surviving Beach Boys (both brothers are long deceased) for a world tour celebrating the Southern California band’s 50th anniversary. But 55 years ago, Brian was just a coastal-community kid who spent most of his non-school time teaching himself to play piano, and to write songs.

With his younger brothers, Carl and Dennis, cousin Mike Love, and another friend, he formed the band that became the Beach Boys. Brian wasn’t a surfer (in fact, he was afraid of the water, and as his mental state deteriorated he even developed a phobia about shower nozzles), but Dennis was a surfer, and he suggested that his older brother write a song about the popular sport, which was enjoying a renaissance among Southern California teens. [In 1916, legendary Hawaiian surfer Duke Kahanamoku surfed the waves off the San Diego community of Ocean Beach, and in the 1920s he and Olympic swimming teammate Tom Blake gave demonstrations up and down the California coast, igniting an interest in surfing that reached a peak in the 1930s with the establishment of “surf clubs” in California's major surfing areas. Surfing hit a lull during World War II, then exploded in popularity in the 1950s and early 1960s.]

On Labor Day weekend, 1961, Murry Wilson and his wife Audree joined friends on vacation in Mexico, leaving Brian in charge of his brothers, with $150 for food and other necessities. Brian took advantage of the ready cash and his brief respite from abuse to rent musical instruments and rehearse his fledgling band on his new song, “Surfin’”.

Although Brian was severely punished when his parents returned home, the band made a bare-bones recording of the primitive song and got it released on the tiny Candix label, owned by a friend of the family. It became a regional radio hit, thus launching the band, and at least a kernel of the sound, that would forever encapsulate the essence of coastal Southern California adolescence — sun, fun, surf, white-sand beaches, girls in bikinis, hamburger stands, hot cars, rock and roll, school, huarache sandals, drive-in theaters, and seemingly endless summer.

But as the rest of the world caught the Beach Boys’ virtual wave, Brian’s muse steered him into increasingly sophisticated waters, his song craft eventually outgrowing not only the audience for disposable ditties about teen fads and fancies, but also the sensibilities of his own band. For a while, Wilson appeased Capitol Records and his nervous bandmates by writing more complex compositions and arrangements, but pairing them with lyrics that clung to comfortable subject matter.

The creative turning point came in 1965 when Wilson’s stage fright and abject fear of flying forced him to stop touring. All he wanted to do was stay home and write music, anyway, so he was replaced in the road band first by a then-relatively-unknown studio guitarist/vocalist, Glen Campbell, and later, permanently, by Bruce Johnston. For the next two years, while the traveling Beach Boys played their sun-drenched songs to sold-out venues, Brian sequestered himself at the piano and in the studio. In 1966, he hired the cream of L.A. session musicians — including members of the famous Wrecking Crew — to bring his evolving compositional ideas to fruition. Among the musicians were drummers Hal Blaine and Jim Gordon, keyboardists Don Randi and Leon Russell, guitarists Tommy Tedesco, Barney Kessel, and Billy Strange, electric bassist Carol Kaye, and acoustic bass players Lyle Ritz and Ray Pohlman.

Kaye’s work, in particular, would prove crucial to realizing the music Brian heard in his head. In addition to writing the Beach Boys’ songs and singing the high lead vocals on many of them, Brian was the band’s bass player, and the melodic, contrapuntal lines he played on the bass, and with his left hand on the piano, were an essential component of their music. Kaye not only replicated those lines, she brought a jazz sensibility and a groove to the sessions that Brian loved.

With his perfectionism in full flower, Wilson exhaustively rehearsed, then recorded the studio musicians playing together, live — sometimes as many as 23 players at a time. When the Beach Boys returned from their latest tour, they found to their dismay that all the instrumentation for the next album had been recorded, that all Brian wanted them to do was execute his meticulously arranged vocal harmonies, and, worst of all, that his music was venturing into deep waters outside the pop mainstream.

Cousin Mike Love, lead vocalist on many of the band’s hits, firmly established himself as the harshest critic of Brian’s more progressive inclinations. He forcefully opined that Beach Boys fans wanted to hear the happy, fun, simpler songs that had made the band famous, and that straying from what he saw as a successful formula could be career suicide.

But Brian won out, and the result was his magnum opus, the 1966 album, Pet Sounds, on which Wilson complemented heart-rending melodies with a rich sonic texture that incorporated his favorite instrumental, animal, industrial, and ambient sounds (i.e. his “pet” sounds). In addition to conventional rock, concert band, and symphony instruments, Wilson used bass harmonica, bicycle bells, vibraphone, temple blocks, harpsichord, Theremin, Hawaiian steel guitar, Coca-Cola cans, barking dogs, train sounds, and other exotica.

Pet Sounds’ trenchant, mature songs about love, yearning, and the loss of innocence signaled Wilson’s official break with the Beach Boys’ teen-tune past. Bowled-over critics hailed the album as a modern masterpiece and Wilson as a musical genius (thus unwittingly planting land mines in his delicate psyche).

Repercussions were felt throughout the music world, forever changing pop songwriting, studio production, the Beach Boys, and Brian himself.

Mike Love felt somewhat vindicated when Pet Sounds didn’t sell as well in the US as previous Beach Boys albums, but it was a huge hit in Great Britain. Paul McCartney recalls being “devastated” when he heard it, because he knew that the bar had been raised to thin-air heights. He took up the challenge by coercing the Beatles into working on a concept album that would become the groundbreaking Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. When that album was heralded as the greatest pop/rock album of all time, Wilson felt compelled to top it, and began work on an ambitious project to be called Smile.

But there were obstacles. The other Beach Boys felt excluded by Brian’s compositional endeavors, and Capitol Records worried about his new music’s commercial viability. Meanwhile, Wilson’s increasing reclusiveness, mental instability, and erratic, substance-modified (legal and illegal) behavior was causing family problems, and the mostly self-imposed pressure to live up to the “genius” label and to one-up the Beatles was exacerbating the problems.

In 1967, feeling besieged by forces inside and outside his own mind, Wilson buckled, and the Smile project imploded. There were rumors (since refuted) that Brian erased the painstakingly, expensively produced tapes in a fit of pique. Smile became the most famous unreleased album of all time, but some of the Smile tracks survived, including several that I played in the June 16 show. One of these was “Our Prayer”, a wordless, a cappella vocal piece that Brian had hoped would open the Smile album on a spiritual note. Barely over a minute long, the recording might be the ultimate example of Wilson’s arranging skills and the Beach Boys’ precisely integrated vocals, both of which had their roots in an experience Brian had had long before he and his brothers formed a band.

One day in 1956, 14-year-old Brian was riding in the car with his mom when a jazzy song came on the radio. The vocal blend of the group, the Four Freshmen, sent Brian through the roof. Audree drove to the nearest record store, where Brian grabbed the new album, Four Freshmen and Five Trombones, and ran to a listening booth in the back. He emerged an hour later, smiling and glassy-eyed, and begged mom to buy him the album.

For the next year, Brian immersed himself in that sound, obsessively learning all the vocal parts and how they moved in relation to each other to create kaleidoscopic harmonies. He also studied recordings by the vocal group the Hi-Lo’s, whose tenor, Clark Burroughs, figured in my radio tribute. Brian taught those harmonies to brothers Dennis and Carl; singing together became a salve for frayed nerves and a calming, late-night distraction as the young siblings lay in the darkened room they shared, having survived another day in a violent home.

When the trio became a quintet, Brian expanded those arrangements to include the other bandmates, then made the guys rehearse until the five-part blend and execution were flawless, thus creating the iconic Beach Boys harmonies. Per his usual approach, Brian taught “Our Prayer” to the Beach Boys in sections, then recorded it in two studio sessions. The recording I aired in the show appeared on the Beach Boys’ 1969 album, 20/20.

Another song from Smile is “Til I Die”, which Brian considers among his best. I didn’t think it was appropriate to talk about the genesis of this song over the airwaves, especially given the Father’s Day issues, but it’s a compelling tale. One night in the spring of 1971, shortly after the Brian-less Beach Boys’ triumphant, career-reviving performance at the Fillmore East, Wilson snuck past his sleeping wife, drove to the beach in Santa Monica, and walked out onto the sand. Overweight and in poor health, his mind and body ravaged by substance abuse and sleep deprivation, and with the psychic demons from a tortured childhood having morphed into malicious voices in his head, he was depressed and preoccupied with death. He’d already given his gardener instructions to dig a grave in his backyard, and was contemplating driving his Rolls Royce off the Santa Monica Pier. [Ed. note: I’m not sure that would’ve been physically possible.]

Instead, as he stood enveloped by darkness, looking out at the black, horizon-less sea, he felt oddly comforted by his comparative insignificance. He thought about the vast ocean stretching to the other side of the earth, and imagined himself alone in a raft in the middle of it. He imagined himself as a cork bobbing on the waves, as a rock in a landslide plummeting into a deep valley, as a leaf being blown about on a windy day, and he was overcome by emotion. He drove home and spent the next several weeks at the piano, trying to find the right combination of rhythm, melody, chords, and lyrics to convey a sense of the catharsis he’d experienced on the beach and the will to live and willingness to persevere that emerged from it.

When he finally played “Til I Die” for the Beach Boys, they hated it. Mike Love, in particular, used salty language in describing the song as a “downer,” and this time Brian’s brothers agreed. Devastated by their lack of understanding of the song’s true meaning, Brian angrily shelved it, but the song ended up on the Surf’s Up album and critics hailed it as one of Wilson’s most personal and evocative songs in many years.

The version of “Til I Die” that I aired in my show was by the Clark Burroughs Group. Following his tenure with the Hi-Lo’s, Burroughs became a first-call vocal arranger, with credits that included two hits by the Association — “Windy” and “Never My Love”. The fact that he’d been part of a group whose vocals provided a blueprint for Brian made him a natural choice to create several vocal arrangements of Brian’s melodies for the CD, Wouldn't It Be Nice: A Jazz Portrait of Brian Wilson. I stitched them together to create a five-minute medley, which included “Cabinessence” (also from the Smile sessions), “Can't Wait Too Long”, “I Went to Sleep”, and “Surf’s Up” (see below). Here are the other Brian Wilson songs I aired on the show:

“Surfer Girl” This was the second song Brian ever wrote, and his first ballad. One day in 1961, 19-year-old Brian was driving to a hot dog stand when the melody for this song took shape in his head. When he got home, he finished the verses, wrote the bridge, and arranged the harmonies. Brian was worried that the song was too pretty to be a follow-up to the Beach Boys’ playful debut single, “Surfin’”, but when the owner of the tiny Candix label heard it, he said, ”That’s a smash if I ever heard one.” As it turned out, the indie label was having money-flow problems, so the Beach Boys used an exit clause in their contract to begin their long association with Capitol Records; “Surfer Girl” became a Top Ten hit in 1963. I aired Don Grusin’s solo-piano interpretation of the song from Wouldn’t It Be Nice: A Jazz Portrait of Brian Wilson.

“Caroline, No” This ballad from the Pet Sounds album boasts one of Wilson’s finest marriages of melody and lyric. In it, the protagonist/singer wistfully realizes that the woman he loves has changed and grown away from him. I aired two instrumental versions of the song in the show. One, by Elliot Easton, guitarist of the ‘80s rock band, the Cars, adheres to the original in tempo and emotional flow, and even opens with a similar, echo-laden “percussion” intro produced by tapping on an acoustic guitar body. Easton, who has played on Brian’s solo albums, achieved a multi-layered effect by de-tuning various 6- and 12-string acoustic guitars. The other was by alto saxophonist Charles Lloyd and his New Quartet from his 2010 CD, Mirror (ECM).

“Don’t Worry Baby” A universally loved pre-Pet Sounds Beach Boys hit. In the show, I aired a Latin-esque treatment by guitarist Steve Khan and singer Gabriela Anders, also from Wouldn’t It Be Nice: A Jazz Portrait of Brian Wilson. The original song perfectly represented the dual-use efforts of Wilson’s “early-middle” period, when he was seemingly writing about teen topics (in this case, reassuring a girlfriend about an imminent and inherently dangerous hot-rod drag race), but actually was writing about the anxieties and insecurities of young love (“don’t worry, baby — everything will turn out alright.”).

“In My Room” Another of Brian’s earliest pre-Pet Sounds songs. Like a lot of kids, Brian frequently retreated to the privacy of his bedroom, but for him it was more like a sanctuary, a refuge from his father’s brutality. He once said that his room was the only place he ever felt safe and unafraid. One day, not long after he’d written “Surfer Girl”, Brian and his lyricist friend Gary Usher played a game of over-the-line on a nearby beach. When Brian got home, Murry Wilson was on another rampage, so Brian made a bee-line to his room, closed the door, sat down at the organ, and wrote this poignant ballad, which appeared on the Beach Boys’ 1963 album, Surfer Girl. An obviously personal song born of fear and hurt, “In My Room” would reach as high as Number 23 on the US charts. In 1999, it was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame, and ranks number 212 on Rolling Stone magazine's “500 Greatest Songs of All Time”. Jazz keyboardist Larry Goldings faithfully captures the song’s emotional essence on the piano rendition I played in the show, from his album, In My Room (2011, BFM Jazz).

“God Only Knows” For a variety of reasons, this is my favorite Brian Wilson song. Paul McCartney went a step farther and called it his favorite song of all time. It’s from the Pet Sounds album, which was released in May 1966, just in time for summer. I remember driving in my car when I heard this single on the radio for the first time; the opening bars, with a French horn melody wrapped around the steady 4/4 figure of a harpsichord/accordion blend, gave me chills — I knew that pop music had forever turned a corner.

Although the refrain, “God only knows what I’d be without you,” seems a secular use of the word “God,” Wilson and lyricist Tony Asher agonized about releasing a song with “God” in the title for fear that it wouldn’t be played on the radio. They hedged their bet by releasing the song as the “B” side of the single, “Wouldn't It Be Nice”. Both songs got ample airplay, but the single barely cracked the Top 40 in America. It was a different story in England, where “God Only Knows” was a massive hit. Reportedly, Lennon and McCartney heard it at a party and immediately left to write songs at Lennon’s place.

I played two versions in this show. The first was an instrumental by multi-reedist Charles Lloyd and pianist Jason Moran from their recent CD, Hagar’s Song (ECM). Lloyd became part of the Beach Boys’ Southern California inner circle in the late ‘60s. The second was Manhattan Transfer’s reflective, almost hymn-like take, from the vocal group’s 1995 album, Tonin’, on the Atlantic label.

“Sail On Sailor” A post-Pet Sounds Beach Boys tune with a strange parentage, and which was an accidental choice for a single. In 1972, the newly revamped Beach Boys took their manager’s advice and went to Amsterdam to record, taking along their families and various hangers-on for what promised to be a long stay in the Netherlands. The only one who didn’t make the trip was Brian, who somehow convinced his wife, Marilyn, to accompany their kids, Wendy and Carnie (later two-thirds of the vocal group, Wilson Phillips) to Holland, promising to follow in a few days. Brian drove to LAX three times before going inside, but his aerophobia soon got the best of him. When his flight arrived in Amsterdam, only his ticket and passport were on his seat. Back in L.A., Brian had calmly walked off the plane before the doors were closed; when Marilyn’s frantic calls got airport security in L.A. to search for Brian, they found him sleeping on a sofa in the first-class lounge.

When the Beach Boys submitted the album, Holland, to Capitol Records, the label balked at the lack of an obvious single and didn’t want to release it. In stepped esoteric songwriter Van Dyke Parks, who claimed that he and Brian had written a song called “Sail On Sailor” that could be a hit. In truth, Wilson had given Parks a few chords and a melodic fragment, but Capitol wanted Wilson to re-take the reins of the band, something he wasn’t interested in doing, so they jettisoned a lesser track to make room for the song, with a new Beach Boy, South African Blondie Chaplin, on lead vocal. Other contributors to the songwriting-by-committee tune included Ray Kennedy, Tandyn Almer, and the band’s manager, Jack Rieley. In my show, I played organist Pete Levin’s reading of the song, from his 2011 CD, Deacon Blues (Motema).

As long as we had jazz musicians interpreting Brian Wilson songs, I thought, “wouldn’t it be nice” to hear Brian return the favor. I aired two relatively recent tunes featuring Brian, the first a concise, “mostly” a cappella vocal treatment of “Rhapsody in Blue”, on which the then-69-year-old Wilson sings all the parts, the second an unfinished Gershwin song that the Gershwin Estate permitted Wilson to finish and record in his style. It’s called “The Like In I Love You”. Both tracks appear on the 2010 CD, Brian Wilson Reimagines Gershwin (Walt Disney Records).

“Don’t Talk (Put Your Head On My Shoulder)” This song from the Pet Sounds album gets new life in a great reworking featuring jazz composer/arranger and multi-instrumentalist Vince Mendoza and guitarist John Abercrombie. In the original, Wilson sings about lovers who have so much past and future “stuff” to think about that it seems best just to remain silent and enjoy the moment. Mendoza said he was immediately drawn to the song’s combination of warmth, melancholy, and foreboding, which he thought was a perfect fit for both his string-arranging sensibilities and Abercrombie’s playing style.

“The Warmth of the Sun” It’s mind-blowing to think that in late 1963 Wilson was writing songs this advanced, in terms of melodic/harmonic interplay, but here’s the proof. It appeared on the largely disposable, car-oriented album, Shut Down, Vol. 2, released a month after the Beatles performed on the Sullivan show, when almost everything in pop and rock was buried under the Beatlemania avalanche. It surprises me that more vocalists haven’t discovered this gorgeous song, but props to Diane Marino for giving it a thoughtful, soulful reading, massaging it just enough to make it hers without, to paraphrase Chuck Berry’s line, losing the beauty of the melody. It’s on her 2008 CD, Just Groovin’ (M&M Records).

“Our Sweet Love” / “Friends” These two contrasting, post-Pet Sounds Beach Boys songs from, respectively, the 1970 album, Sunflower, and the 1968 album, Friends, make a nice pair when arc-welding together by pianist Eliane Elias as her contribution to the Wouldn’t It Be Nice: A Jazz Portrait of Brian Wilson project.

The centerpiece of the legendary, abandoned 1966 Smile album was supposed to have been a song with the purposely ironic title, “Surf’s Up” — ironic because the tune, co-written by Brian Wilson and Van Dyke Parks, had nothing to do with surfing and was, in fact, more in league with other genre-busting, modular art songs Brian had written in the late ‘60s, such as “Good Vibrations” and “Heroes and Villains”. When the song was played for the Beach Boys, lead singer Mike Love angrily denounced what he considered intentionally abstract lyrics, prompting Parks to storm out and disassociate himself from the ultimately doomed Smile project.

Fast-forward to the spring of 1971: the Beach Boys, minus Brian, play a triumphant concert at the Fillmore East on a bill with the Grateful Dead, a performance that reconstitutes their hipness quotient among the rock cognoscenti and fuels their preparations for a new album, to be called Landlocked. In need of material, they would dust off a version of “Surf’s Up” that Brian had recorded for a 1967 Leonard Bernstein TV special, add their distinctive harmonies, and coax Brian to re-record the lead vocal. It worked so well that the name of the 1971 album was changed from Landlocked to Surf's Up. Jazz pianist David Kikoski was inspired to name his own 2001 album Surf's Up, and in my show I played his extended interpretation of the Wilson/Parks song.

Post Script: Many of the reviews I’ve read of the recent Beach Boys reunion/anniversary tour make a point about Brian Wilson’s semi-presence, about him appearing to be “out of it” and seeming less than thrilled to be involved, about his negligible contributions to the stage shows. Inasmuch as Brian’s mental chaos, broken by intermittent lucidity and impressive productivity, has been well-documented for more than four decades, I see no point in dwelling on that.

My wife and I and another couple shared a front-row table at the 2005 Hollywood Bowl concert at which Wilson and his crack band of a dozen or so mostly young musicians performed songs from his ageless catalog, then took an intermission, and returned to play the music originally written for the Smile project. Brian needed a teleprompter, his keyboard playing was more show than dough, and he occasionally stared at the adoring throng of Bowlers as if they were a hallucination. But the music was exhilarating, the program was impeccably paced and coordinated, and the audience gave Wilson the kind of unconditional love he never got as a child. It was a transcendent night of music under the stars, and nothing else mattered.

I have little patience for the cruel jokes about what a mental mess Brian became. I know he got into drugs in his 20s and 30s and acted erratically, that he would embarrass his young daughters by shuffling out to their school bus in his pajamas, that he ballooned to over 300 pounds and “heard voices,” etc. In fact, I saw him up-close-and-personal years after his infamous meltdown, at a point in his life when he was all but forgotten. I was selling advertising in Beverly Hills in 1979-80 to support my songwriting pursuits, and I spent my weekdays meeting with proprietors at the toniest shops on and around Rodeo Drive. Every day in “B Hills” I bumped into celebrities — OJ Simpson (weekly), Jack Lemmon, author Ray Bradbury, Dustin Hoffman, Loretta Swit, Mel Torme, etc.

One day, I was waiting to cross an intersection on Rodeo, and as I gazed at the small group of people waiting on the other side of the street, I realized that one of them was Brian. It was hard to miss him because he was huge, and his unkempt hair and beard stood out among the chic shoppers. I couldn’t believe that when the sign changed to “Walk” I was going have a chance to say “hello” to one of my music idols. But as I watched him amble toward me, looking bloated and disheveled, glancing around as if he didn’t know where he was, my excitement gave way to a profound sadness. Before we almost brushed shoulders, he looked at me with the most forlorn expression. I couldn’t bring myself to speak.

I’d rather not dwell on that aspect of Brian Wilson’s life. I prefer to marvel at his talent and to enjoy the great music he has given to the world at such a horrendous personal cost. I hope that my show did him justice.

[If you missed the June 16, 2013 (3-5 p.m.) installment of Johnny D’s Jazz Journal titled, “In His Room: Jazz Smiles on Brian Wilson”, you can hear it in archived form by signing up for Jazz88.3’s online “Speakeasy” — the free, interactive online “club” that gives you access to on-demand, “Premium Content” and puts you on an exclusive list of people who have a chance at online giveaways.

Just click on the “Speakeasy” graphic on our home page at http://jazz88.org and provide an email address and password. KSDS won’t send you anything and your info will not be shared or sold to anyone — it’s just an extra benefit for Jazz88.3 listeners. Once you’re on the Speakeasy page, scroll down just a bit and you’ll see a list of “Full Programs”. My show is at the top of the right column. Just click on it and you’re listening to that week’s show.]