The title and theme of my show on Sunday, May 12, 2013 (3-5 p.m. PDT) is “Deja Entendu”. You know that “deja vu” (French for “already seen”) is that strange feeling that you’ve experienced something in the exactly the same way before. “Deja Entendu” is the sense that you’ve heard something before. The theme was inspired by an email I received in February from Erie, Pennsylvania-based jazz guitarist and music store proprietor Jim Lynch. He was listening to the streaming version of my show when I aired pianist Benny Green’s tune, “Benny's Crib”. Until I identified the artist and the track, Jim assumed that he was listening to an interesting arrangement of the Jimmy Giuffre composition, “Four Brothers”.

In my email response, I said that over the years I’d noticed a number of distinct similarities between one jazz composition and another. Some of that is intentional, and there’s even a word for it; the term “contrafact” refers to a piece of music in which a new melody is played over a familiar chord progression. But why would someone do that?

Jim’s friend, jazz guitarist/composer Frank Singer, mentioned the territorial struggle in the 1940s between the performing rights societies, ASCAP and BMI; they collect royalties and distribute them to artists when their music is performed live or aired on stations like Jazz 88.3 — ostensibly, it’s a way to ensure that artists are compensated when their music is used. ASCAP (American Society of Composers and Publishers) was founded in 1914, and pretty much had a monopoly on licensing until 1939, when it demanded a 100-percent increase in fees. The National Association of Broadcasters responded by creating BMI (Broadcast Music Incorporated), both to offer an affordable alternative to ASCAP and to license emerging genres of music that ASCAP wasn't interested in — namely, blues, jazz, rhythm and blues, gospel, country, folk, Latin, and, eventually, rock and roll. Radio stations essentially banned ASCAP recordings from the airwaves, giving BMI a huge win and making it a major player overnight.

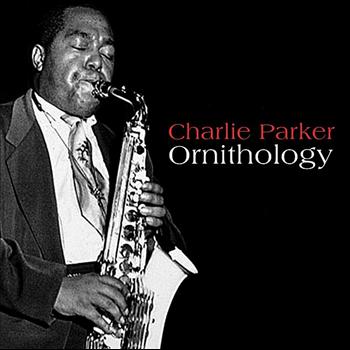

But this posed a serious problem for recording artists, who, of course, wanted and needed airplay. When they realized that the vast library of ASCAP-licensed songs were off-limits, the more creative artists circumvented that obstacle by taking advantage of a loophole in the laws then governing intellectual property: while melodies could be copyrighted, the harmonic substructure could not be. This proved to be a windfall for beboppers, who simply applied new melodies to the chord changes of familiar songs, changed the titles, and registered them as their own compositions. And that is the origin of many of the contrafacts of the 1940s, including “Ornithology”, written by Benny Harris and Charlie Parker and recorded by Parker in 1946, six years after Morgan Lewis and lyricist Nancy Hamilton wrote the song, “How High the Moon”, for the 1940 Broadway revue, Two for the Show. The songs share the same chordal movement, with Bird’s overlaid melodic materials differing from the previously established tune enough to preclude legal problems.

It even can be said that this development did as much to put bebop itself on the map as it did to launch BMI, because it played right into the bebop mindset. In swing and other kinds of music up to that time, improvisation was modular, relegated to pre-ordained sections, similar to the (usually short) cadenza passages in classical music. Bebop, however, reversed that model — musicians would play the head, or main theme, of a piece, then break out into extended, exploratory, melodically complex soloing over the tune’s harmonic foundation, before finally returning to re-state the head.